Having first been built in 1767, Bell House has a rich history, a long list of previous inhabitants - and its fair share of ghost stories

Read moreThomas Wright and the City of London

Thomas Wright, the first resident of Bell House, took a diligent role in civic affairs at a time when the City was developing rapidly and confidently. The Seven Years War had just ended, paving the way for Britain’s global expansion.

Read moreDyslexia Overview

Louise Wood takes an overview of Dyslexia - where have we come from and where are we going?

If you are new to the world of dyslexia as a parent, teacher or young person who has been recently diagnosed, it is worth remembering that dyslexia is relatively new to us all.

The Past Struggle for Recognition

A team at the University of Oxford, under the leadership of Dame Maggie Snowling, has recently begun a project to understand the history of dyslexia; the evolution of the science, the political struggle for acceptance and the everyday experience. Details are available on this link: https://dyslexiahistory.web.ox.ac.uk/home

A German physician first diagnosed ‘word blindness’ in 1877 and the term dyslexia was coined by German ophthalmologist Rudolph Berlin in the same year, but recognition came very much later. The British Dyslexia Association was formed in 1972, the same year that a key report on children with specific learning difficulties was sceptical about dyslexia’s existence. Government recognition surfaced in a parliamentary debate in 1987 but progress in education arrived with the Rose Report on dyslexia and literacy in 2009. Protection for those with dyslexia in the workforce came finally with the UK Equality Act of 2010.

Dyslexia Today, The Facts

For an overview of where we stand today, a summary by the Driver Youth Trust in the British Dyslexia Association Handbook provides some hard and sobering facts:

* 10% of children in this country are dyslexic, 4% severely so;

* One in eight children fail to master the basics of reading and one in five fail to master the basics of writing by the end of primary school;

* At secondary level, over a third of young people failed to achieve the expected level of a grade A to C in GCSE English in 2011;

* One in six people in the UK struggle with literacy, their reading level falling below that expected of an 11-year-old;

* Six million UK adults are functionally illiterate, meaning that they cannot read a medicine bottle, food label or fill out a job application form.

In addition to the personal heartache, the economic costs of this situation are considerable:

* Research by KPMG found that each illiterate person, by the age of 37, has cost the taxpayer an additional £45,000 in extra costs relating to education, unemployment support and the criminal justice system;

* The Every Child a Chance Trust estimated that poor literacy costs the UK up to £2.5 billion per year;

* Low levels of literacy make it harder to find employment. One study found 4 out of 10 unemployed people using Jobcentre Plus were dyslexic;

*Around half the prison population struggle with poor literacy and one in five people in prison are understood to have dyslexia.

Research amongst teachers shows that they are still not receiving the support they need to identify and help those with dyslexia and other specific learning needs:

* More than a third of teacher training providers (35%) spent less than a day training teachers how to support children who struggle with literacy;

* 60% of teachers surveyed by the Driver Youth Trust did not feel satisfied that their initial teacher training provided them with the skills they need to teach those who struggle to learn to read and write.

The future, five reasons for optimism

Will the future be any better? The British Dyslexia Association held its 11th International Conference in April 2018 and the feeling from this conference was that there are a number of reasons to be positive and hopeful.

The first is the sheer weight of international and multidisciplinary research now going into this field, particularly that capitalising on developments in neuroscience and genetics. Pure research is complemented by practical projects across all age ranges in education and increasingly in the workplace. Supporting the emotional well being of those with dyslexia is also an important current research theme.

Secondly, the debate is now framed more around discussions of neuro-diversity. Parents and educators have long felt that children with dyslexia don’t always fit into a neat pigeonhole but, like all children, have different learning styles, weaknesses but also strengths. Comorbidity or the frequent co–occurrence of specific learning issues is widely acknowledged too. Recognition of this level of complexity helps drive more appropriate interventions and focuses us on starting with an understanding of each of us as an individual.

Use of the term neuro-diversity has also led to a focus on the positive strengths of those who often struggle with literacy. These centre on creativity, adaptability and resilience. A number of public role models and success stories have emerged around this theme. One speaker put it this way ‘Our creativity is our competitive edge’, ‘There’s a reason why this DNA exists’ and ‘I will put my money on a dyslexic every time’. Valuing neuro-diversity is helping the stigma to melt away.

Thirdly, these advances coincide with the boom in information technology, which allows the development of new tools to support those with special learning needs. This article was written using a dictation device; scanning pens proliferate, organisational and touch-typing software is widely available. Ideas can be shared widely and easily using film and other visual media.

Finally, information technology also leads to economic and employment opportunities, which have not existed before and which allow those with dyslexia to circumvent the traditional career structures based around exams, employment forms and ongoing written tests. The creative economy is the one least amenable to mechanisation. Entrepreneurial skills have an outlet rarely seen before.

The statistics are sobering and the prospects for those with dyslexia can sometimes seem overwhelming, especially when it is new to you. But the seeds are definitely there for a surge forward to ensure the future can be very much brighter than the past.

Here at Bell House we hope to play our part by supporting educators, parents and those with dyslexia and other specific learning needs.

Matt repairs the ha-ha

Having repaired the beautiful Georgian wall that divides Bell House from College Road, Matt has returned to work on one of the last surviving ha-has in London. Built in 1767, it was designed to protect the garden from passing livestock (sheep and cattle were driven along College Road to market in London). The name ha-ha is thought to derive from the expression of surprise as people discovered what they thought was uninterrupted grass was actually a hidden wall. Unlike a fence it is invisible from Bell House, leaving views which would have stretched for miles in Georgian times.

Working outside in this hot weather brings its own issues. Matt must ensure that the traditional lime mortar he uses (its flexibility helps protect the brickwork from future damage) does not dry out too quickly. Lime mortar gains its strength, in part, from carbonation: the absorption of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Just because a mortar is dry does not mean that it has carbonated and if the pointing dries before enough carbonation has taken place, the mortar will crack and weaken. So Matt has been starting work very early, spraying the brickwork with water to slow down the process, and finishing before the heat of the day affects the mortar. Come past Bell House around 7am and he will already be at work. Luckily because he is a traditional craftsman, working only with his hands, there are no intrusive noises to disturb the neighbours. Once Matt has worked his way along the ha-ha he will work back again, replacing any missing bricks.

The retaining walls of the ha-ha, which stretch towards the road and support the pavement outside Bell House, are buckled and need complete replacement. Together with Nicholas Garner, Matt has devised a structure that will support the load placed on the walls but also be visually sympathetic to the location. A hidden metal and concrete structure will be faced with recycled Georgian bricks.

We hope that our commitment to repairing and maintaining Bell House in this sustainable and traditional manner will help preserve the house for the next 250 years of its history.

Thinking Differently About Dyslexia

Louise Wood reflects upon books that approach dyslexia in a positive way and discusses the new theory of neuro-diversity.

Anyone who has puzzled over the different take on a problem or issue by a partner, child or colleague will tell you that we all think differently. But now we understand a great deal more from neuroscience about why this might be the case. The term neuro-diversity has been coined to describe this characteristic.

Four recent books take up the idea and expand upon how those with dyslexia think differently, in particular more creatively. In a world that is changing in favour of adaptability, creativity and resilience, those with dyslexia may have the competitive edge.

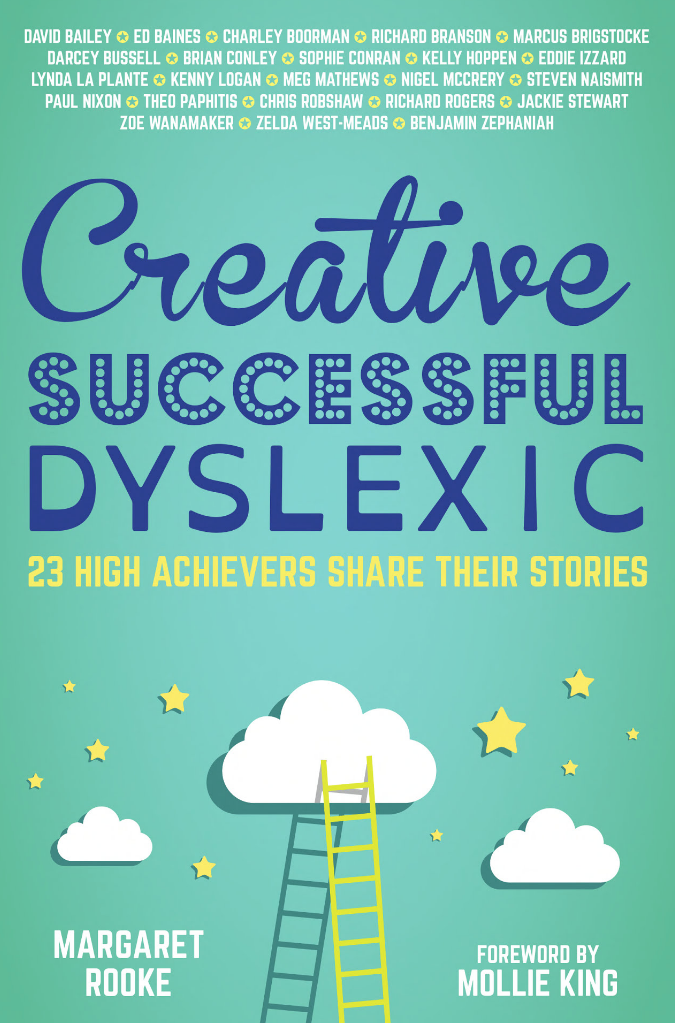

Successful: Richard Branson, Darcy Bussell and Benjamin Zephaniah

Margaret Rooke, an established writer and mother of a dyslexic daughter, decided that she wanted to identify the characteristics of those with dyslexia who go on to achieve happiness and success in their chosen field. She interviewed 23 people, including poet Benjamin Zephaniah, entrepreneurs Richard Branson and Theo Paphitis, architect Richard Rogers and performers Eddie Izzard, Marcus Brigstocke and Darcy Bussell. Their insights are individual and inspirational but can all be grouped under the title of her book, Creative, Successful, Dyslexic.

Buoyed by the response to this book, Rooke went on to ask, what about ordinary young people? What strategies work for them? This resulted in a series of in-depth interviews with more than 100 children from 7 different countries for a book called Dyslexia is My Superpower (most of the time). The interviews show the importance of self-insight, building self-confidence and the many ways dyslexic children seek out what works for them. The fantastic illustrations by the children will be familiar to any parent of a dyslexic child and show that the written word is not the only way to make a powerful point.

But what of the world of work?

If you have seen Tiffany Sunday’s TEDx talk you will know what a persuasive public speaker she is and how passionately she feels that her own dyslexia has given her Dyslexia’s Competitive Edge, the title of her latest book. She argues that the future favours the entrepreneur and spells out exactly why dyslexics make excellent entrepreneurs. The words creativity and resilience come up again and also the importance of role models and mentors. Her thought-provoking rallying call is that computers will replicate neuro-typical thinking easily, but those who think less typically will be gold dust in the new technological economy.

For the British economy, built on engineering, ingenuity and creativity, tapping the widest range of talent in future is a cause we can all get behind.

Margaret Malpas MBE provides an overarching viewpoint, gained from a career in human resources and working with the British Dyslexia Association. In her book Self-Fulfillment with Dyslexia, A Blueprint for Success she has carefully researched the characteristics that enable adult dyslexics to achieve their full potential. These include finding the right niche, tapping your passion, drawing on coping strategies built up in early life and recognising atypical problem solving and creative skills. Significantly Malpas drills down to break the term creativity into its component parts - not just the moment of insight, but also the editing and follow through of ideas.

Encouragingly for those of us who support dyslexic friends and relatives Malpas and the fellow authors show how we as employers and family can make a big difference to the success of those with dyslexia by fostering self belief and providing emotional support. Together with self-awareness, these provide the emotional tool kit for success.

It’s important to note that no one is saying that being dyslexic makes life easy or that those with dyslexia have any inbuilt intellectual superiority or inferiority. But certainly the combined message of these four books, spotlighted at the recent British Dyslexia Association International Conference, is that those with dyslexia should draw more than a little comfort and a lot of excitement about the possibilities ahead.